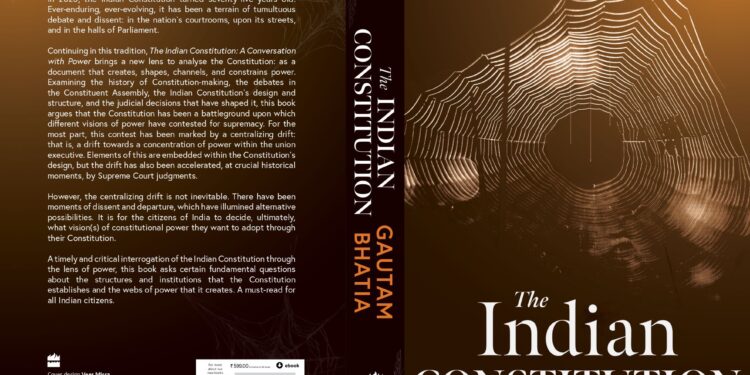

In his thought-provoking book, The Indian Constitution: A Conversation with Power (HarperCollins India, 2025), Gautam Bhatia, a prominent Indian constitutional lawyer and scholar, offers a fresh and incisive perspective on one of the world’s longest and most dynamic constitutions. Published to mark the 75th anniversary of the Indian Constitution’s adoption in 1950, this 345-page work reframes the document not merely as a legal framework but as a living “map of power” that shapes, channels, and constrains the flow of authority in India’s democracy. Written in clear, accessible prose, the book is a timely and critical exploration of how India’s constitutional history has unfolded, with lessons that resonate far beyond its borders. For global readers, Bhatia’s analysis provides a universal lens on the tensions between centralized power and democratic ideals, making it a must-read for anyone interested in constitutionalism, governance, or the delicate balance of power in modern democracies.

A New Approach to Constitutional Analysis

Bhatia’s central argument is that the Indian Constitution is a “terrain of contestation” where competing visions of power—centralized versus decentralized, executive-driven versus pluralistic—have clashed over seven decades. Unlike traditional legal scholarship that dissects constitutional provisions in isolation, Bhatia examines the document through six interconnected axes: federalism, parliamentarianism, pluralism, institutions, rights, and the role of “the people.” This framework allows him to trace how power has been organized and contested in India, revealing a persistent “centralizing drift” toward the Union executive at the expense of states, local bodies, and individual freedoms.

The book’s strength lies in its ability to make complex legal concepts accessible to a global audience. Bhatia avoids dense jargon, instead weaving together historical context, judicial decisions, and philosophical insights to tell a compelling story. He argues that this centralizing drift is not an accident but is embedded in the Constitution’s text and design, accelerated by key Supreme Court judgments at critical “inflection points.” For international readers, this narrative echoes broader debates about federalism and executive overreach in democracies like the United States, Brazil, or Nigeria, where tensions between central and regional powers are ever-present.

Key Themes and Insights

Bhatia’s analysis is structured around landmark cases and constitutional moments that have shaped India’s power dynamics. One of the book’s standout sections explores the 2019 abrogation of Article 370, which revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, downgrading it to a Union Territory. Bhatia critiques the Supreme Court’s role in upholding this move, arguing that it cemented the centralizing drift by prioritizing executive authority over federal principles. He contrasts this with the dissenting opinion of Justice Subba Rao in the 1960 case *State of West Bengal vs Union of India*, which advocated a more balanced federal structure—a vision that could have altered India’s constitutional trajectory.

Another key focus is the Emergency period (1975–1977), when then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi suspended fundamental rights and concentrated power in the executive. Bhatia examines how the Constitution’s “silences and ambiguities”—such as its provisions for emergency powers—enabled this authoritarian turn. He notes that while the 44th Amendment later curbed some of these powers, it failed to address the root cause: the Constitution’s inherent trust in the executive. This insight is particularly relevant for global readers, as it mirrors debates in other democracies about emergency laws and their potential for abuse, as seen in contexts like Turkey’s post-2016 coup measures or the U.S. Patriot Act.

Bhatia also delves into the concept of “constitutional common sense,” a set of unspoken assumptions that guide judges, lawyers, and policymakers. He argues that this common sense has often favored centralized, homogenous power over pluralistic and distributed alternatives. By drawing on thinkers like Antonio Gramsci and Roberto Gargarella, Bhatia situates India’s experience within a global discourse on how legal systems shape societal power structures. This comparative approach makes the book a valuable resource for readers in countries grappling with similar issues, such as South Africa’s post-apartheid constitutionalism or Germany’s federal balancing act.

Strengths and Contributions

One of the book’s greatest achievements is its refusal to treat the Constitution as a sacred, untouchable document. Bhatia, a Delhi-based advocate who has argued in landmark cases like the challenge to Article 370 and the right to privacy, brings a practitioner’s rigor to his analysis. He meticulously dissects Supreme Court judgments, such as the *Kesavananda Bharati* case (1973), which established the “basic structure” doctrine, and interpretations of Article 356, which allows the central government to dismiss state governments. His critique is unflinching: neither the Constitution’s framers nor the judiciary are neutral arbiters; both have been complicit in the centralizing drift.

For a global audience, the book’s clarity and structure are exemplary. Each chapter begins with a clear outline of its goals, making it easy to follow even for readers unfamiliar with Indian law. Bhatia’s ability to connect specific cases to broader themes—like the tension between individual rights and state power—ensures the book’s relevance to anyone studying democratic governance. His discussion of federalism, for instance, resonates with Canada’s debates over provincial autonomy or Australia’s struggles with state-federal relations.

The book also shines in its global comparisons. Bhatia draws parallels with other constitutions, noting that India’s centralizing drift is not unique but part of a broader pattern in post-colonial states. He cites Argentina’s constitutional scholar Roberto Gargarella to argue that centralized power does not inherently protect rights, challenging the notion that a strong executive is necessary for social reform. This perspective invites readers from diverse contexts to reflect on their own constitutional systems.

Areas for Improvement

While the book is a triumph of clarity and insight, it is not without flaws. Some readers may find the lack of footnotes, with endnotes relegated to the back, cumbersome for tracking sources—a minor but noted inconvenience in reviews. Additionally, while Bhatia emphasizes that the centralizing drift is not inevitable and can be reversed, he offers fewer concrete solutions for how citizens or institutions might achieve this. A deeper exploration of potential reforms—such as strengthening state autonomy or judicial independence—could have added practical weight to his critique.

For international readers, the book’s focus on India-specific cases, like Article 370 or the *Kesavananda Bharati* judgment, may occasionally feel dense without more context. While Bhatia does an admirable job of explaining these cases, a brief primer on India’s constitutional history might have made the book even more accessible to those unfamiliar with the region.

Why It Matters Now

Published in 2025, as India marks 75 years of its Constitution, the book arrives at a pivotal moment. Recent political developments—such as the 2024 general election, where the Constitution became a lightning rod for debate—underscore its timeliness. Bhatia highlights contemporary issues, including the use of laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) to suppress dissent and the controversial role of state governors, which have sparked global concerns about democratic backsliding. His analysis of these trends offers a sobering reminder of how constitutional frameworks can either safeguard or undermine democracy, a lesson relevant to nations like Hungary, Poland, or Brazil, where similar dynamics are at play.

The book’s global appeal lies in its universal question: how do constitutions balance power in diverse, complex societies? Bhatia’s answer—that power is not static but contested, shaped by choices that can be revisited—empowers citizens everywhere to engage critically with their own systems. As he writes, “It is for us citizens to decide, ultimately, what vision(s) of constitutional power we want to adopt and give to ourselves”.

Conclusion

The Indian Constitution: A Conversation with Power is a bold, lucid, and deeply engaging work that transcends its Indian context to speak to global debates about democracy, power, and constitutionalism. Gautam Bhatia’s ability to blend legal expertise with accessible storytelling makes this book a vital resource for students, scholars, policymakers, and citizens worldwide. While it could benefit from more practical solutions and additional context for non-Indian readers, its rigorous analysis and universal themes make it a standout contribution to constitutional scholarship. For anyone seeking to understand how power operates within democratic systems—or how it can be reimagined—this book is an essential read.

Rating: 4.5/5

Where to Buy: Available at local bookstores or online through HarperCollins India, Amazon.in, or other major retailers.